Abstract

“Hybrid” nouns are known for being able to trigger either syntactic or semantic agreement, the latter typically occurring outside the noun’s projection. We document and discuss a rare example of a Hebrew noun that triggers either syntactic or semantic agreement within the DP. To explain this and other unusual patterns of nominal agreement, we propose a configurational adaptation of the concord-index distinction, originated in Wechsler and Zlatić (2003). Morphologically-rooted (=concord) features are hosted on the noun stem while semantically-rooted (=index) features are hosted on Num, a higher functional head. Depending on where attributive adjectives attach, they may display either type of agreement. The observed and unobserved patterns of agreement follow from general principles of selection and syntactic locality.

Similar content being viewed by others

Notes

Both determiners are also specified [concord | number sg] but this is redundantly satisfied in the cases under consideration. Further gender restrictions apply which are not relevant to the present point.

(7c) and (8b) are possible, of course, on the plural reading (the friend and the colleague are distinct).

This unhappy ambiguity is a constant source of disgruntlement, so much that the word is often avoided in feminist circles.

One might speculate that the emergence of the ‘owner’-sense in (16b) is a response to the general dispreference for the CS (as in (15b)) among speakers of Modern Hebrew.

The agreement pattern is insensitive to the semantic class of the adjectives (intersective, non-intersective and intensional), as (17)–(20) make clear. See also (60) below.

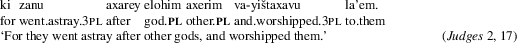

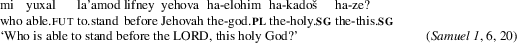

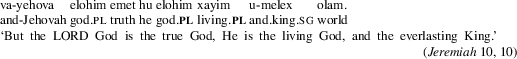

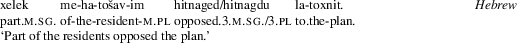

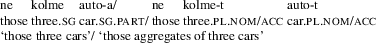

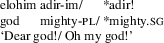

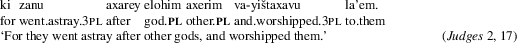

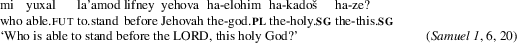

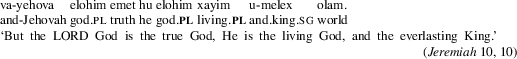

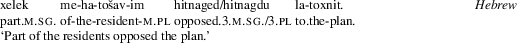

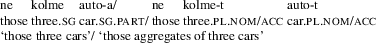

The phenomenon of morphologically plural nouns with singular reference is recognized in traditional Hebrew grammars as pluralis excellentiae, which is akin to pluralis majestatis (royal we), the idea being that the plural suffix can function as an intensifier. The paradigm example is the noun elohim ‘god(s)’ in Biblical Hebrew (other examples are adonim ‘Lord(s)’, trafim ‘household god(s)’ and behemoth ‘giant beast(s)’, the last one taking the feminine plural suffix -oth). Consider elohim. Although morphologically plural, it could refer to either a single god (normally, Jehovah) or a plurality of gods (normally, idols); the singular form, eloha, was also in use. (i) is an example of plural reference (notice the plural pronoun that takes elohim as antecedent), parallel to (17b); (ii) is an example of singular reference, cooccurring with a singular attributive adjective, parallel to (17a); and (iii) is an example of singular reference, cooccurring with a plural attributive adjective, parallel to (18a)/(19a).

-

(i)

-

(ii)

-

(iii)

-

(i)

It is a moot question whether encyclopedic information of the kind stored in sex and count is directly encoded in linguistic representations. I follow the hpsg practice in assuming it is, but nothing crucial hinges on this assumption. Even if the relevant information is grammar-external, it is still somehow mapped to the linguistic index features, and the mapping is systematic.

Although we focus on [number], recall that [gender] is also unspecified; see (16a–b).

The diagrams in (27) envision agreement as an asymmetric directional relation, in line with a derivational view of syntax (e.g., minimalism). A symmetric representation, however, is equally possible, as in declarative grammars (e.g., hpsg).

I thank Stephen Wechsler for this example.

By implication, it is possible that NumP is missing in pluralia tantum nouns and [number] is lexically specified on N. Note that cardinal numerals do not occupy NumP but a distinct, higher projection, that we may label CardP. CardP must be higher than NumP because semantically cardinals are functions over plural individuals (Heycock and Zamparelli 2005). Some terminological confusion is caused by the fact that studies of Greenberg’s Universal 20 routinely refer to the projection of cardinals as NumP (e.g., Cinque 2005; Steddy and Vieri 2011; Abels and Neeleman 2012). I keep to the original sense of NumP (that is, Ritter’s sense). See also the discussion of Finnish and Lebanese Arabic data in Sect. 5.4.

A formally similar proposal, motivated by entirely different facts, has been put forward in Danon (2013). Danon discusses an agreement alternation involving QPs, attested in many languages, where agreement targets that are clausemate to the QP agree either with the Q head or with its NP (often partitive) complement.

-

(i)

-

(ii)

Danon analyzed what looks like (non-local) agreement between T (or v) and the NP complement of Q in (i) as standard local agreement with Q. The latter is endowed, on top of its inherent concord number feature (singular in (i)), with an unvalued index number feature, which is valued by the index number feature of the head noun (plural in (i)). On the present analysis, this dependency would be broken into a two-step agreement chain: D-Num and Q-D. Note that (ii), on the bound variable reading of we, introduces an additional puzzle: The verb may show [3Sg] agreement while the bound pronoun shows [1Pl] agreement (possibly via feature transmission; see Postal and Collins (2012:169–174) for a syntactic account, contrasting with Rullman’s semantic account).

-

(i)

There may be a deeper reason why adjectives cannot bear typed index features. If we assume that typing implies exhaustivity, a category with index features should specify gender, number and person. But adjectives universally lack the person feature, possibly for principled reasons (Baker 2008, 2011), hence would not be typed with index features. Valuation, of course, does not require exhaustivity, hence adjectives as agreement targets can be (and often are) less specified than their controllers.

The structure in (34) is neutral on the phrase-structural status of attributive adjectives—adjuncts or specifiers. For similar proposals that break up the nominal space into two agreement zones, see Ouwayda (2013, 2014) (on [number]) and Pesetsky (2014) (on [gender]). I discuss their data and analyses in Sects. 5.4 and 6.1.

An interesting question concerns agreement on predicative adjectives and participles, categories unspecified for [person]. If these elements agree directly with the subject nominal, they are expected to be able to target concord features. If, however, they first form an agreement relation with the auxiliary verb, they will be forced to enter index agreement. Variation is expected and indeed may be real (see Wechsler and Zlatić 2003:53–56 and “The Predicate Hierarchy” in Corbett 2006:230–233).

This analysis is parallel to the hybrid analysis of another class of D-heads—relative pronouns—developed by Wechsler and Zlatić (2003:56–59). The Serbian/Croatian relative pronoun koja ‘who (nom)’, for example, spells out inherent concord features but simultaneously mediates index agreement between the head noun and the predicate in the relative clause.

Attributive adjectives cannot attach above D, presumably for reasons of semantic type (Adj takes NP-meanings as arguments), hence Zone C is off limits for them.

The complexity added to standard feature systems by the concord-index distinction raises technical questions for the notion of feature matching (Danon 2013). In what sense are the typed features [concord | number] and [index | number] and the untyped feature [number] (on adjectives) “the same thing”? Some equivalence is needed to guarantee, for example, that a single morpheme may spell out either one of the first two and that both may agree with the third. One possibility is to make [number] (and by extension, [gender] and [person]) the superfeature and concord and index its subfeatures. Another possibility (suggested by Danon) is to allow complex values, e.g., [concord [number sg]].

It is conceivable that the entire Zone A would be rolled-up and sandwiched between NumP and adjectives in Zone B. Whether or not the resulting configuration would bleed index agreement on the latter is unclear, since the deeply embedded N would not c-command Num and so might not count as closer to the probing adjectives. This derivation can be excluded in principle if Num is a “freezing head” in the sense of Shlonsky (2004), similarly to cardinal numerals in Hebrew. In Shlonsky (2012) this property reduces to the absence of the movement-trigger, an unvalued [D] feature, from Num.

See Steriopolo and Wiltschko (2010) for a related proposal that distributes gender features over three distinct heads in the nominal projection.

Is [index | gender] always hosted on Num, even when it matches [concord | gender]? This contradicts (40) but may conform with Bantu-specific morphosyntax. These typological issues merit detailed investigation and must be left open for now.

The model in (34) is clearly close in spirit to a very traditional dichotomy in grammatical analysis—between NP-internal and NP-external agreement (the former even labeled differently as “concord”). It is, however, refined in the present analysis by the tripartite, rather than binary division of the clausal space. Corbett (2006:228) explicitly argues against such divisions. The argument is based on the tendency of relative pronouns to show greater “semantic” agreement than attributive adjectives, which are like them NP-internal, and even greater than predicates, which are NP-external (the so-called “Agreement Hierarchy”). The force of this argument, however, rests on the vagueness of the category “NP”, which, for us, is really an extended projection. Note that relative clauses are adjoined to the maximal projection of the “traditional” NP, which is surely high enough to contain NumP (and any projection up to DP). Thus, relative pronouns are predicted to manifest index (=semantically grounded) agreement in the general case—unlike attributive adjectives. Furthermore, unlike nonverbal predicates which are unspecified for [person], relative pronouns are specified for this feature (even if invisibly), owing to their pronominal origin. Thus, in principle the former can but the latter cannot avail themselves of concord agreement. These considerations then make Corbett’s Agreement Hierarchy fully consistent with a rigid, domain-sensitive theory of agreement.

The singular morphology of the numeral itself is not the outcome of agreement but an inherent, interpretable number feature; when plural, it produces a “layered” plurality:

-

(i)

-

(i)

Note that if the analysis of determiners in Sect. 5.1 is correct, cases of mixed D-Adj agreement (e.g., (11)) do not fall together with the present Adj-Adj cases (contra Corbett). This is because determiners, on the present view, always agree both in concord and index (their features are typed, unlike those of adjectives; see (33)), and merely spell out one of these feature sets. In principle, a concord-specified D may attach outside a Zone B adjective, giving rise to (what looks like) a violation of Corbett’s Distance Principle. Nothing of the sort should be possible for Adj-Adj stacking. Whether this nuanced contrast is actually realized in any language is an intriguing, open question.

Why nouns following TD-numerals are not marked plural in Lebanese Arabic is a puzzle Ouwayda (2014:112) leaves unanswered.

Adding a numeral to the subject in (55a–b), makes no difference. Note that Hebrew lacks the TD/non-TD divide that Arabic has and treats all numerals greater than one the same way.

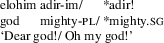

There are no idiom-forming adjectives that occur with be’alim. elohim ‘god’, another noun in this class (see footnote 6), does occur with an adjective in an idiom, and indeed, only plural agreement (reflecting concord number) is compatible with the idiomatic reading.

-

(i)

It is difficult to draw general conclusions from this single example.

-

(i)

In (61a), the collective NP only symmetrically c-commands D; in (61b), the associate does not raise covertly (den Dikken 1995); in (61d), the inverted predicate must reconstruct at LF (Heycock 1995). Note that the assumption that agreement is checked at LF is at odds with the bare minimalist view of LF as an interface level that only contains semantically contentful information.

Obviously, W&Z’s theory draws a number of grammatical distinctions between concord and index features that are fruitfully exploited elsewhere (e.g., the fact that the former is a head feature and the latter is not, the fact that the latter attaches to an index and the former does not, etc.). The point is that none of these indisputable distinctions is of any help in making sense of the data at hand.

A non-derivational (but still crucially configurational) alternative way of deriving these results might restrict the Agree operation to downward probing. Thus, even in the presence of a higher Num head that bears the index features, an attributive adjective in Zone A would only be able to Agree with the lower head, N, in concord features. This solution, however, runs afoul a growing body of research that shows upward probing to be a viable, in fact common option for agreement (Rezac 2003; Baker 2008; Zeijlstra 2012; Harley 2013).

References

Abels, Klaus, and Ad Neeleman. 2012. Linear asymmetries and the LCA. Syntax 15: 25–74.

Baker, Mark. 2008. The syntax of agreement and concord. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Baker, Mark. 2011. When agreement is for number and gender but not person. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29: 875–915.

Bernstein, Judy. 1991. DPs in French and Walloon: Evidence for parametric variation in nominal head movement. Probus 3: 101–126.

Bernstein, Judy. 2001. The DP hypothesis: Identifying clausal properties in the nominal domain. In The handbook of contemporary syntactic theory, eds. Mark Baltin and Chris Collins, 536–561. Oxford: Blackwell.

Borer, Hagit. 2005. Structuring sense, Volume 1: In name only, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brattico, Pauli. 2010. One-part and two-part models of nominal case: Evidence from case distribution. Journal of Linguistics 46: 47–81.

Brattico, Pauli. 2011. Case assignment, case concord, and the quantificational case construction. Lingua 121: 1042–1066.

Carstens, Vicki. 2000. Concord in minimalist theory. Linguistic Inquiry 31: 319–355.

Carstens, Vicki. 2008. DP in Bantu and Romance. In The Bantu–Romance connection: A comparative investigation of verbal agreement, DPs, and information structure, eds. Cécile de Cat and Katherine Demuth, 131–165. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2005. Deriving Greenberg’s Universal 20 and its exceptions. Linguistic Inquiry 36: 315–332.

Cinque, Guglielmo. 2010. The syntax of adjectives: A comparative study. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Corbett, Greville G. 1979. The agreement hierarchy. Journal of Linguistics 15: 203–224.

Corbett, Greville G. 1983. Hierarchies, targets and controllers: Agreement patterns in Slavic. London: Croom Helm.

Corbett, Greville G. 1987. The morphology/syntax interface: Evidence from possessive adjectives in Slavonic. Language 63: 299–345.

Corbett, Greville G. 1991. Gender. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Corbett, Greville G. 2006. Agreement. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Danon, Gabi. 2011. Agreement and DP-internal feature distribution. Syntax 14: 297–317.

Danon, Gabi. 2013. Agreement alternations with quantified nominals in Modern Hebrew. Journal of Linguistics 49: 55–92.

Delfitto, Denis, and Jan Schroter. 1991. Bare plurals and the number affix in DP. Probus 3: 155–185.

Dikken, Marcel den. 1995. Binding, expletives and levels. Linguistic Inquiry 26: 347–354.

Doron, Edit, and Irit Meir. 2013. Construct state: Modern Hebrew. In The encyclopedia of Hebrew language and linguistics, ed. Geoffrey Khan. Leiden: Brill Online.

Dryer, Matthew S. 1989. Plural words. Linguistics 27: 865–895.

Frampton, John, and Sam Gutmann. 2006. How sentences grow in the mind: Agreement and selection in an efficient minimalist syntax. In Agreement systems, ed. Cedric Boeckx, 121–157. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Harley, Heidi. 2013. Feature matching and case and number dissociation in Hiaki. Revista Linguistica 9: 1–10.

Heim, Irene. 2008. Features on bound pronouns. In Phi theory: Phi-features across modules and interfaces, eds. Daniel Harbour, David Adger, and Susana Béjar, 35–56. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Heycock, Caroline. 1995. Asymmetries in reconstruction. Linguistic Inquiry 26: 547–570.

Heycock, Caroline, and Roberto Zamparelli. 2005. Friends and colleagues: Plurality, coordination and the structure of DP. Natural Language Semantics 13: 201–270.

Jerro, Kyle, and Stephen Wechsler. 2015. Person-marked quantifiers in Kinyarwanda. In Agreement from a diachronic perspective, eds. Jürg Fleischer, Elisabeth Rieken, and Paul Widmer, 147–164. Berlin: de Gruyter.

Julien, Marit. 2005. Nominal phrases from a Scandinavian perspective. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

King, Tracy H., and Mary Dalrymple. 2004. Determiner agreement and noun conjunction. Journal of Linguistics 40: 69–104.

Koopman, Hilda. 1999. The internal and external distribution of pronominal DPs. In Beyond principles and parameters, eds. Kyle Johnson and Ian Roberts, 91–132. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

Kramer, Ruth. 2014. Gender in Amharic: A morphosyntactic approach to natural and grammatical gender. Lingua 43: 102–115.

Kratzer, Angelika. 2009. Making a pronoun: Fake indexicals as windows into the properties of pronouns. Linguistic Inquiry 40: 187–237.

Munn, Alan, and Cristina Schmitt. 2005. Number and indefinites. Lingua 115: 821–855.

Ouwayda, Sarah. 2013. Where plurality is: Agreement and DP structure. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS), eds. Stefan Keine and Shayne Sloggett. Vol. 42, 81–94. Amherst: GLSA.

Ouwayda, Sarah. 2014. Where number lies: Plural marking, numerals and the collective-distributive distinction. PhD dissertation, USC.

Pearce, Elizabeth. 2012. Number within the DP: A view from Oceanic. In Functional heads: The cartography of syntactic structures, eds. Laura Brugé, Anna Cardinaletti, Giuliana Giusti, Nicola Munaro, and Cecilia Poletto. Vol. 7, 81–91. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Pesetsky, David. 2014. Russian case morphology and the syntactic categories. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Pesetsky, David, and Esther Torrego. 2007. The syntax of valuation and the interpretability of features. In Phrasal and clausal architecture: Syntactic derivation and interpretation (In honor of Joseph E. Emonds), eds. Simin Karimi, Vida Samiian, and Wendy K. Wilkins, 262–294. Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Postal, Paul, and Chris Collins. 2012. Imposters: A study of pronominal agreement. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Rezac, Milan. 2003. The fine structure of cyclic agree. Syntax 6: 156–182.

Ritter, Elizabeth. 1991. Two functional categories in noun phrases: Evidence from Modern Hebrew. In Syntax and Semantics 25, 37–62. New York: Academic Press.

Ritter, Elizabeth. 1992. Cross-linguistic evidence for number phrase. Canadian Journal of Linguistics 37: 197–218.

Ritter, Elizabeth. 1993. Where’s gender? Linguistic Inquiry 24: 795–803.

Ritter, Elizabeth. 1995. On the syntactic category of pronouns and agreement. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 13: 405–443.

Rooryck, Johan, and Guido J. Vanden Wyngaerd. 2011. Dissolving binding theory. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Rullman, Hotze. 2010. Number, person and bound variables. Slides for a talk given at Radboud Universiteit, Nijmegen.

Shlonsky, Ur. 2004. The form of Semitic noun phrases. Lingua 114: 1465–1526.

Shlonsky, Ur. 2006. Rejoinder to “Pereltsvaig’s head movement in Hebrew nominals: A reply to Shlonsky”. Lingua 116: 1195–1197.

Shlonsky, Ur. 2012. On some properties of nominals in Hebrew and Arabic, the construct state and the mechanisms of AGREE and MOVE. Rivista Di Linguistica 24: 267–286.

Smith, Peter W. 2012. Collective (dis)agreement. In Conference of the Student Organisation of Linguistics in Europe (ConSOLE) XX, eds. Enrico Boone, Martin Kohlberger, and Maartje Schulpen, 229–253. Leiden: University of Leiden.

Smith, Peter W. To appear. The syntax of semantic agreement in British English. Ms., University of Connecticut.

Steddy, Sam, and Samek-Lodovici Vieri. 2011. On the ungrammaticality of remnant movement in the derivation of Greenberg’s Universal 20. Linguistic Inquiry 42: 445–469.

Steriopolo, Olga, and Martina Wiltschko. 2010. Distributed GENDER hypothesis. In Formal studies in Slavic linguistics: Formal description of Slavic languages 7.5, eds. Gerhild Zybatow, Philip Dudchuk, Serge Minor, and Ekaterina Pshehotskaya, 155–172. New York: Peter Lang.

Valois, Daniel. 1991. The internal syntax of DP and adjective placement in French and English. In North East Linguistic Society (NELS), ed. Tim Sherer. Vol. 21. 367–381. Amherst: GLSA.

Valois, Daniel. 2006. Adjectives: Order within DP and attributive APs. In The Blackwell companion to syntax, eds. Martin Everaert and Henk Van Riemsdijk. Vol. 1, 61–82. Oxford: Blackwell.

Wechsler, Stephen. 2011. Mixed agreement, the person feature and the index/concord distinction. Natural Language and Linguistic Theory 29: 999–1031.

Wechsler, Stephen, and Larisa Zlatić. 2003. The many faces of agreement. Stanford: CSLI.

Zeijlstra, Hedde. 2012. There is only one way to agree. The Linguistic Review 29: 491–539.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Rights and permissions

About this article

Cite this article

Landau, I. DP-internal semantic agreement: A configurational analysis. Nat Lang Linguist Theory 34, 975–1020 (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9319-3

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

Issue Date:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11049-015-9319-3